SMALL ISLAND STATES PROJECT

update: 09/20

Index

A rebel and a Queen: Two Voices from the Pacific

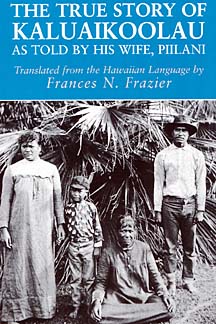

The True Story of Kaluaikoolau: As Told by His Wife, Piilani. Translated by Frances N. Frazier. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. Distributed for the Kauai Historical Society, 2001. $14.95 ISBN: 0-9703293-0-X (paper) and 0-9607542-9-6 (cloth). 160 pp. Illustrations.

Queen Salote of Tonga: The Story of an Era, 1900E965. By Elizabeth Wood-Ellem. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2001. $22 ISBN 0-8248-2529-2 (paper). 376 pp. Illustrations.

Reviewed by Robert Seward[1]

The voices of Pacific women are heard here in two very different books. In one, The True Story of Kaluaikoolau: As Told by His Wife, Piilani, a native Hawaiian describes her familys experiences in defiance of provincial authorities, just before the turn of the twentieth century. In the other, Queen Salote of Tonga: The Story of an Era, 1900E965, by Elizabeth Wood-Ellem, it is the biography of Polynesian royalty.

Kaluaikoolau takes place in the period following the American overthrow of Queen Liliuokalani. Hawaiian life is gripped by the panic surrounding Hansens diseaseotherwise known as leprosythe only contemporary comparison probably being the early days of the AIDS epidemic, when contagion was widely feared. Piilani, in this first-person narrative, translated sympathetically by Frances Frazier, recounts how her husband comes to realize that he, as well as their son, has contracted the dread disease. In a heartrending moment, he vows never to be separated from his family, never to succumb to exile. In turn, the wife chants her own pledge:

With me, my husband Kaluaikoolau,

Me au kuu Kane Kaluaikoolau,

With me, my child Kaleimanu,

Me au kuu Kane Kaleimanu,

With me, you two, until the bones are laid to

rest,

Me au olua a waiho na iwi,

With me, you two, until the final disappearance!

Me au olua a nalo mau

loa!

When the authorities come to take her husband awayeither dead or alive, in which case he will be deported to the leper colony on Molokaithe family has already made up their mind. In an initial confrontation a white police official is shot. They flee to the mountains of Kauai. In pursuit, the local militiawho are from illustrations, also whitetrack the family to their hiding place on a cliff, firing upon them with guns and cannon. But Piilanis husband is the superior marksman, and several men in the militia are felled.

The family lives in the mountains in solitary isolation, on the run, for three and a half years before the disease claims Piilanis husband and son. She buries them in, as she puts it, their native soil,Ewhich she covers withEspan class=SpellE>lehua blossoms, ti leaves, ferns and fragrant leaves of trees. In anguish and with lamentation, Piilani leaves the mountains and reunites with her family and community.

Some years later she recounts her story, which is transcribed into written Hawaiian and published around 1906. The tale is sufficiently compelling that Jack London based a short story of his own on it.

The story has assumed the proportions of a great legend of the Pacific. It is the story of the strength and commitment of a Hawaiian woman, told in her own voice and rendered into English with sensitivity for the time when oral tradition held sway. Biblical references entwine with native Hawaiian belief. Of course the translation dives into sentimentality, yet it would be a shame to judge it by contemporary ways of thinking, by a contemporary construction of a gendered order. Piilanis tale contains its own convictions and political meanings from the turn of the centuryand confusions not unlike our own.

In the end it is Piilanis story, her devotion and love, that captures ones imagination.

Queen Salote of Tonga is quite another tale. While not hagiography, this life story of the beloved queenEis written with the approval of the Tongan royal family.

In opening the Tongan parliament in 1937, the queen declaimed that There is not in the world a little Kingdom like Tonga, peaceful, contented and happy.EThat wasnt true then, and it certainly isnt true these days either. Tonga is one of the only remaining monarchies in the worldstill controlled by the king and nobilityand it is not without significant problems. Nevertheless, there is much instructive and compelling material in Elizabeth Wood-Ellems biography.

The author draws not only from official resources and oral accounts but from her own intimate knowledge of Tongan society, where she grew up and lived for many years. There are few studies that are better on the complexities of marriage, the role of rank and status, and the intricate kinship relations among the aristocratic families of the kingdom. That the queen maneuvered these intricacies is a wonder, and the details carry the narrative of the biography.

Of necessity, perhaps, Wood-Ellem tells the by now tiresome story of Queen Salote as she attended the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953. If you have been to Tonga, youve heard the story many times: It rained and the Tongan Queen didnt raise the roof of her carriage; she got wet but preserved her natural dignity.EThat incident made the international news.

In the end, it is not anecdotes of this kind that lead to an interest in Salote. Politics and the complicated social structure of the kingdom are related as they intertwine the life and reign of the queen, which ended in 1965. The interplay of religionthe queen was a fervent Christian and the kingdom still isand gender play throughout the pages of the book.

The queen may have been regarded as kind,Ebut she was no pushover. She let her son, the crown prince, know that she didnt appreciate his male-centric, European views. In Tongan society, as in the Tongan family, it is the sister who determines the destiny of the group and is the ultimate authority on social relationships. Brothers govern the land and its bounty.

Salote was cognizant of a twentieth-century change in attitudes toward women, particularly those of high and middle rank. While she herself represented the traditional Tongan privilege afforded women, she observed women losing ground to a masculine ideology, to fakapalangi ways where Tongans aspired to a European lifestyle, and cautioned against it.

Women should maintain their dignity, she believed. And in the modern world women should take their place besidenot behindmen, just as they did in traditional society. The queen was far in advance of the womens movement.

In this kingdom located 2 hours and 45 minutes flying time northeast of New Zealand, Salote played a prominent role in founding womens organizations, not only for religious purposes but also with the aim of improving health and the domestic economy. She was astute in using these organizations for her larger political purpose. She discouraged, for example, Tongan women joining the Pan Pacific and South-East Asian Womens Association because they were not yet ready to join an international organization.E Instead she set up her own organization for nation-building.

Quotidian events in the life of the queens subjects, however, are far removed from this biography, and there is little offered of their lives except from the royal perspective. But in a period when the controversies over globalization confront us, the queens concerns about the erosion of Tongan valueslove, respect, common helpfulnessin the service of economic gain are instructive. This is a narrative that has continuity with the present time.

Salotes legacy would seem to persist, to a degree, as Tongans seek to preserve their identity, even as the contemporary democracy movement struggles to take hold. The kingdom is quite unlike other parts of the colonized Pacific, although the British and missionaries did their best to muck about. (The Friendly Islands, as Tonga is also known, was once a British protectorate.)

These days the kingdom is suing the Kings American court jester,Ea low-level mutual funds manager, for mismanagement (or theft) of a $24 million government trust fund. Human rights organizations accuse the government of stifling the press. There are more gloomy reports.

Queen Salote of Tonga is indeed the story of an era, a period when a powerful woman ruled. The biography shows that womenat least this queencan be a potent force in shaping change as well. And the queens view of the advantages of a society where everyone knew their placeEstill endures. As Wood-Ellem writes, In Salotes view, Parliament was an aberration of history, rather than an arm of government.E

To invoke a wider cultural and political context, pay close attention to detail in this biography, and dont go romantic over a Pacific Polynesian queen. Salote stabilized the fractious country of feuding aristocrats, nobles and lesser chiefs, but neither democracy nor free markets found their ways to these shores. That was true during Salotes time, and its generally true now too.

The book is, nevertheless, a welcome read, a biography to reflect on when bad news about the kingdom drives out the good.

[1] This review appeared in Pacific Reader, An Asian Pacific North American Review of Books (International Examiner), 622 South Washington Street, Seattle, Washington 98104. Fall 2002